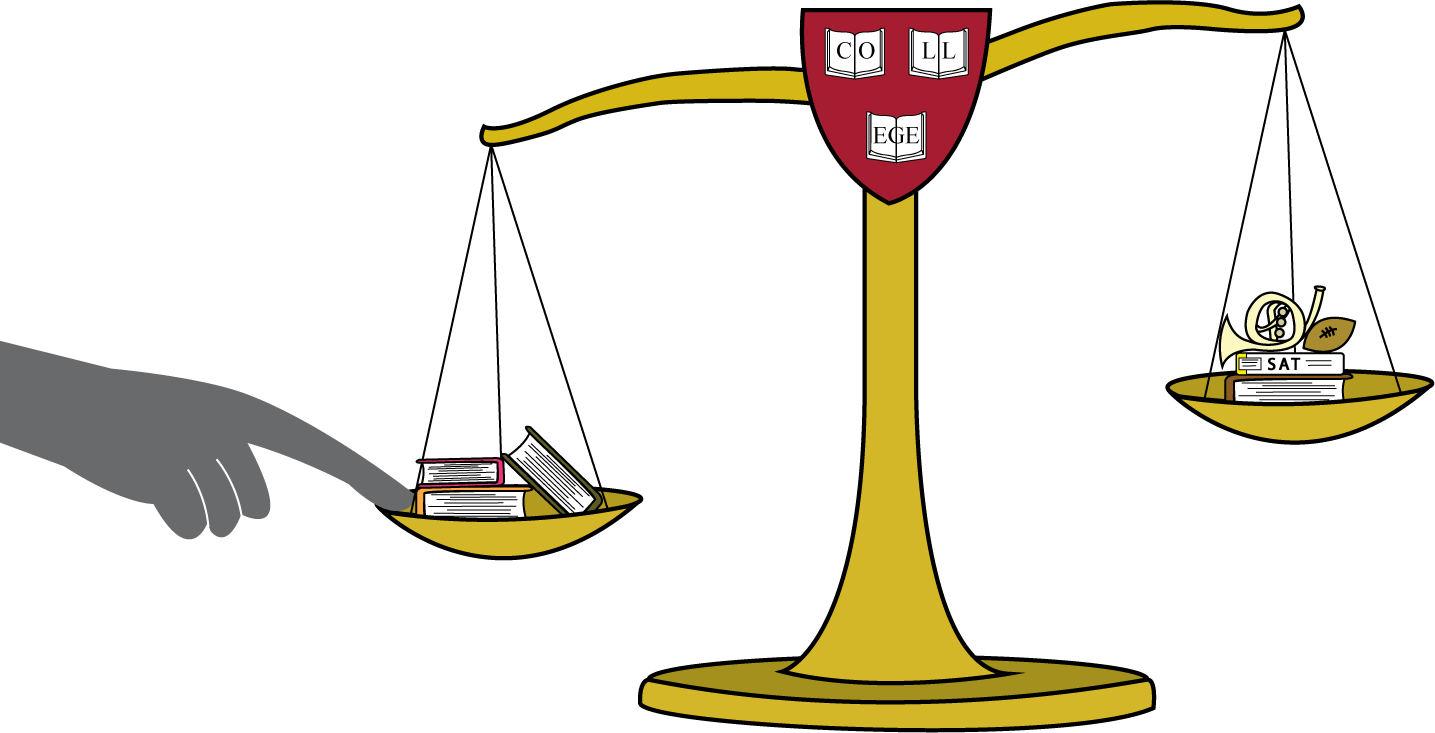

The case for balance

Opinions divided as Supreme Court prepares to hear case on affirmative actionGraphic by Kevin Xiang, Staff Writer

Anshi Vajpayee, Opinions Editor & Kevin Xiang, Staff Writer

*Dave is an alias for a Northview student who has chosen to remain anonymous. The Messenger staff chose this name for them in order to protect their identity. Any similarity to a real student name is purely coincidental.

On March 6, 1961, soon after taking office, President John F. Kennedy signed what is thought to be the first contemporary policy on affirmative action, Executive Order 10925. In the midst of high racial tension in the civil rights era, this policy sought to push businesses to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.”

Today, the series of laws and acts dubbed “affirmative action” has expanded to include other underrepresented minority groups, including those of sexuality and gender.

According to Northview U.S. History and TAG teacher Michael Martin, affirmative action first sought to level the playing field for groups subjected to historical discrimination, but now–– especially in the college admissions process––the previous race-conscious process has blurred into race discrimination.

On Jan. 24, 2022, the conservative-majority Supreme Court announced that it will hear an appeal of affirmative action in Harvard University’s and the University of North Carolina’s admissions processes. In the Harvard University case, a group of Asian American plaintiffs, called Students for Fair Admission, sued Harvard University for unlawfully discriminating against Asian American applicants and violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“We do need to at least put a thumb on the [admissions] scale and offer some dispensation for [marginalized students] not being able to perform at the same level as a very privileged white or Asian student from a school like Northview,” Martin said. “But they're creating a situation where it's not just a thumb––it's throwing the whole rubric away.”

Martin argues that a system that helps underprivileged students have a fair chance at admission to top universities, or a metaphorical “thumb on the scale,” is necessary; however, he believes universities should make a concerted effort to create a transparent process.

“That's when Americans start having concerns no matter what side of the political aisle they’re on,” Martin said. “They don't understand or know or have any information about what criteria decisions are being made that could affect their lives.”

Currently, Harvard University does not have any requirements for potential applicants, a calculated decision that is intended to give all students from unconventional and diverse backgrounds a chance to apply. This, Martin believes, does not work in the students’ favor as they are sometimes left unclear about whether their application is deemed valid at all.

“That's where Harvard does not want to be pinned down,” Martin said. “They want to be able to make exceptions to their own policies. If they just feel like they have a tremendously dynamic person who's applying for something, they’re like ‘well, they're so dynamic, we'll figure it out.’”

Asian American senior Dave* agrees and believes that while including marginalized groups to diversify student bodies is important, universities should prioritize merit above all other factors.

“When I see cases online about big universities like Harvard discriminating specifically against Asian pre-med applicants like myself, I can’t help but feel that the system is against me,” Dave said.

Dave is referring to instances in Harvard University admissions where despite outperforming white applicants in other areas, Asian applicants are consistently rated lower for personal metrics. These include qualities like personality, a pivotal point that Students for Fair Admission has included in its primary evidence for race-based discrimination.

“I understand that this holistic admissions process includes more than just your statistics and grades and test scores, but Harvard has consistently fallen to the stereotype of a brain-dead Asian immigrant who’s probably going to be a doctor or engineer,” Dave said. “I just want to be evaluated for my own merit fairly.”

Elizabeth Lake, a language arts teacher, believes the notion of race-based discrimination stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of the function of affirmative action.

“There are people who believe that affirmative action means quotas for different racial, gender, sexuality, or ability groups,” Lake said. “Based on that misconception, they believe that it's wrong to say you can only have a certain number of each group of people, but it's not what affirmative action is.”

Lake stresses the importance of understanding the goal and methods of affirmative action. She says the policy was implemented to ensure equity of access for everyone, especially in a world where racism and classism exist, drawing on her own personal experience to define her beliefs on the matter.

“So much of what I grew from and learned at the University of Georgia was not what I took from the classroom but what I learned from meeting people who had a variety of different life experiences,” Lake said. “If the college had just been looking at SAT scores and grades, I probably would have met a lot of people from schools like mine and with experiences similar to mine, and even if we might have looked different, we would have had a lot of the same life experiences growing up.”

Principal Brian Downey agrees with this sentiment. He did not attend a college where there was a diverse set of voices, and he feels disappointed to have missed out on a valuable experience.

“Oftentimes, colleges as their own unique institutions believe in creating an environment in which the student body is diverse because they want the kids to be faced with and challenged with different voices, different experiences, and different cultures so they graduate with an experience that prepares them for the world,” Downey said.

For Black senior Kunashe Rwizi, this is exactly what she seeks to tap into in college. When she was offered admission to the University of Chicago’s early action class of 2026, a flurry of emotions pulsed through her: shock, happiness, and hope for future decisions. Above all, though, she was proud to have been recognized for her accomplishments throughout high school.

“After I got into UChicago, it kind of gave me a little confidence boost,” Rwizi said. “Maybe I could get into some of these other top schools. I felt nice.”

Rwizi, an active soccer player, believes affirmative action did not help her get in; rather, it only gave her the opportunity for her talents to be recognized.

“Someone said that I'm smart, but affirmative action would get me the rest of the way, like I'm not smart enough to get there by myself,” Rwizi said. “I'm smart enough that affirmative action will take care of the rest.”

Considering the history of the U.S., Rwizi believes the use of affirmative action in the college admissions process helps even the playing field for groups that were historically discriminated against.

“Ending affirmative action will prevent [marginalized students] from being given the opportunity and the platform to be able to make a difference,” Rwizi said. “Circumstances that are out of their control would get them stuck in a cycle because no one will ever be given the opportunity to get out and break that cycle.”

Since the process of college admissions is complex and not fully transparent, it is difficult to discern the impact of affirmative action on individual applications, according to Lake. Even so, she has seen this scapegoating being taken too far in some cases.

“I have seen students who fervently believed affirmative action policies are what kept them from getting in somewhere because it was easier for them to believe that a policy is what kept them from getting in and not the true randomness that is college admission,” Lake said.

She has also seen students who got into good colleges being overlooked by others who believed affirmative action was what helped them get in.

“It should never be that brilliant students are made to feel lesser than by their peers,” Lake said. “That is a thing that hurtful people say to their peers when they want to feel better about themselves.”

Rwizi agrees and feels that she would be the same applicant to these colleges regardless of her skin color. She believes that the strength of her application speaks for itself.

“Affirmative action didn't make me look better to colleges,” Rwizi said. “It didn't change any of my extracurriculars. It didn't bump up my grades any few points. It just allowed [admissions officers] to see me at all.”